Table of Contents

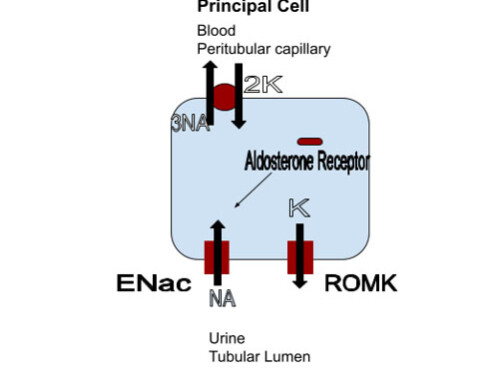

Just like in hyperkalemia

A useful framework for evaluating nephrology electrolyte issues like hypokalemia is:

- Too little in

- Cellular shifts

- Too much out

Before we get to that there also can be artifactual hypokalemia. This happens when the potassium in the body is normal, but enters the cells ex vivo, in the collection tube. So just like pseudohyperkalemia

There can be pseudohyperkalemia.

This happens when there are a lot of metabolically active cells (think leukemia with severe leukocytosis). The potassium enters these cells after phlebotomy resulting in a low potassium result.

Too little in

- Malnourished states

This is an unusual cause of hypokalemia. Turns out the kidneys are good at their job. In this case the job is preserving potassium when intake is low.

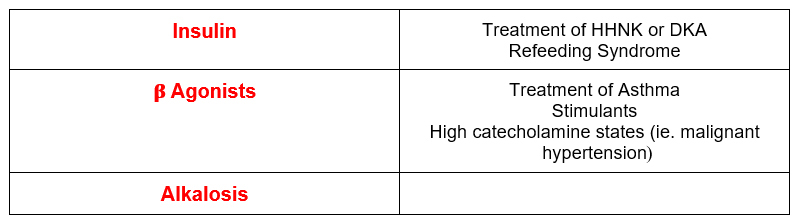

Cellular shifts

Most potassium in the body is intracellular, and there are pathologic states that can enhance this process resulting in hypokalemia.

It’s easy for you to think about this, you already know it. Think about how you treat hyperkalemia.

It’s fun to know about rare stuff, so here’s one for you: Hypokalemic periodic paralysis.

What happens here is there is an exaggerated response to stress, exercise, or a high carbohydrate meal (with resultant normal insulin release) or exercise leading to excessive potassium uptake by cells. There is an autosomal dominant hereditary form and an acquired form that may be associated with hyperthyroidism. Think about this in a board question describing weakness and hypokalemia in a person of Asian or Mexican heritage. If check TSH is an answer, pick it.

Too much out

Three questions I ask to aid in the differential of hypokalemia.

- Are the kidneys acting appropriately?

- What’s the acid-base status?

- What’s the blood pressure?

Are the kidneys acting appropriately?

What’s appropriate for the kidneys to do? If the patient is hypokalemic the kidneys should be preserving potassium. How do we tell if the kidneys are acting appropriately?

- Old teaching: 24 hour urine potassium. This should be less than 25-30 mmol per day. (That is as low as the kidneys can go).

- Why not a random urine potassium (mmol per liter)? Because even if the random urine potassium is low, the 24 hour urine potassium could be high (if the patient is polyuric). The opposite can also be true. The random urine potassium could seem high, but if the 24 hour urine output is low the total or absolute urine potassium may be low.

Thing is, doing a 24 hour urine hour urine for K is a pain and didn’t really happen too much. Fortunately there is a simpler way to assess the kidney’s response to hypokalemia.

- New way: Random urine potassium/creatinine ratio. Using our assumptions about extrapolating what a 24 hour creatinine should be (as we do when assessing proteinuria. This is enough to give us an idea of how well the kidneys are preserving potassium.

- A potassium:creatinine ratio of < 13 meq/gram suggests the kidneys are preserving potassium. This will happen both if the hypokalemia is due to too little in, transcellular shifts or extrarenal losses (typically gastrointestinal losses).

Gastrointestinal Causes of Hypokalemia

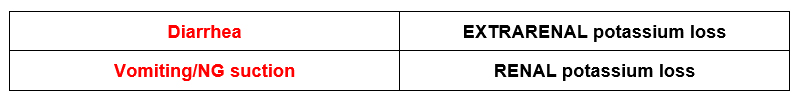

Remember upper gi losses (ie vomiting/ NG suction), cause RENAL potassium wasting. Why? Because they are associated with metabolic alkalosis.

Metabolic alkalosis ➞ urinary bicarbonate excretion ➡ increased urinary potassium excretion

Bicarbonate (HCO3– ) is negatively charged; it brings something positively charged (like potassium) with it.

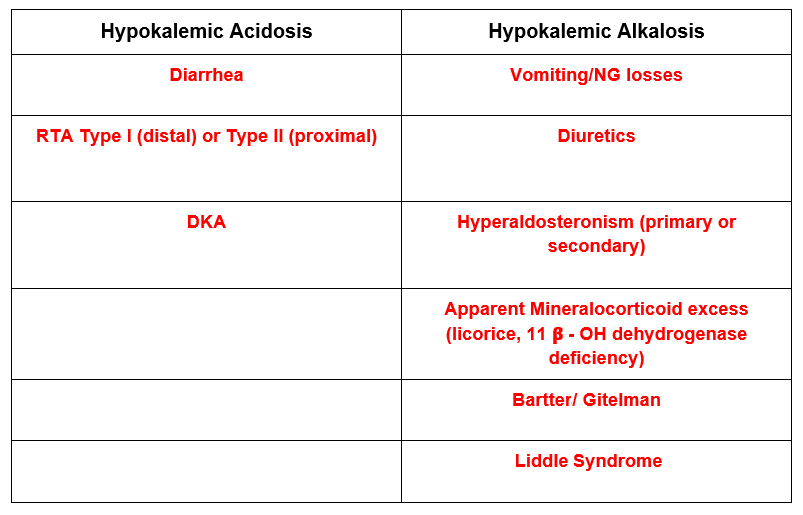

What’s the acid-base status?

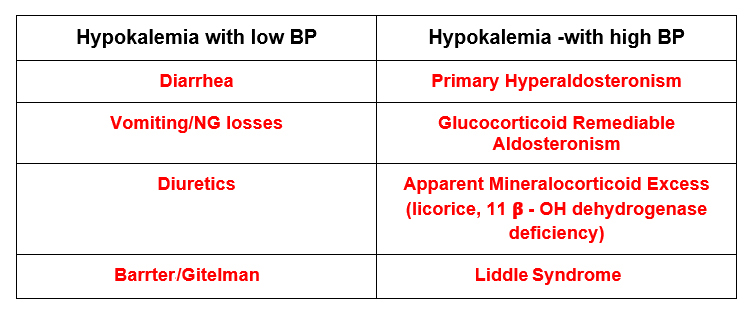

What’s the blood pressure?

Summary

This is how I approach elucidating the cause of hypokalemia. First is there decreased intake, transcellular shifts, or increased excretion? Next, are the kidneys preserving potassium appropriately? Then is there an associated acid base disturbance? Finally is there an associated decrease or increase in blood pressure?

This approach will allow a comprehensive accurate diagnosis.