Table of Contents

Minimal change disease is a glomerular disease that causes nephrotic syndrome and the first one I’ll be reviewing in this series.

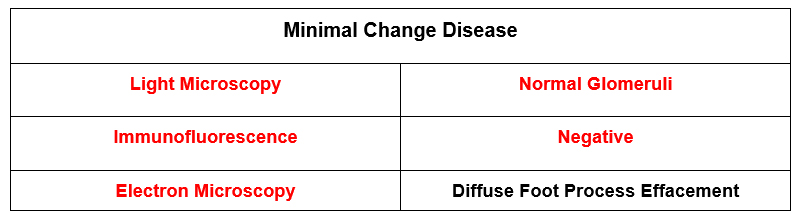

Called minimal change as the glomeruli look normal (there are minimal glomerular changes) on light microscopy. Also referred to NIL disease, not sure why they called it that. NIL might be an old fashioned way of saying nothing. Can also use NIL as an acronym Nothing In Light, normal light microscopy as noted above.

There are 3 standard parts of a kidney biopsy:

- Light Microscopy

- Immunofluorescence

- Electron Microscopy

For minimal change disease the diagnosis is made on Electron Microscopy.

On electron microscopy what is seen is diffuse foot process effacement. The foot processes are the part of the glomerular capillary wall that attach the podocytes to the glomerular basement membrane. This is a structural sign that the podocyte is damaged (so the protein leaks into the urine). In many glomerular diseases this process is focal, in minimal change disease it is diffuse.

Clinical Characteristics

- First of all it often happens in young people. It is the most common cause of nephrotic syndrome in children. For this reason, children with nephrotic syndrome often don’t get a kidney biopsy. They assume this is the diagnosis and only biopsy if they don’t respond to treatment.

- It can happen in adults too. About 10% of minimal change disease is in adults. Usually relatively young adults (average age like 45).

- Abrupt onset (like days to a week or two) of full blown nephrotic syndrome. That is edema, hypoalbuminemia and severe proteinuria. The proteinuria and hypoalbuminemia are relatively severe (like 10 grams protein and albumin < 2.5 g/dl.

- There can be associated AKI (in 25-35% of cases). This is not a nephritic or Rapidly Progressive Glomerulonephritis (RPGN). It is Acute Tubular Necrosis (ATN). This is attributed to a hypooncotic state with low blood pressure and renal edema.

- Often steroid responsive with rapid, abrupt clinical response.

Anecdotally, the cases I have seen have been young patients (in their 20’s) who develop acute onset of edema and are found to have nephrotic syndrome with preserved kidney function.

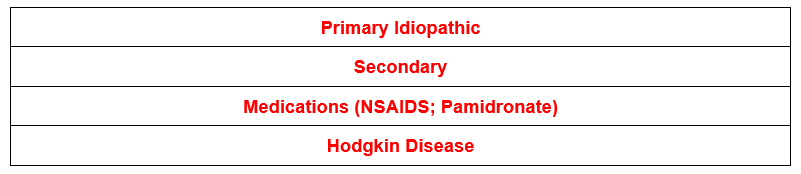

The interstitial nephritis caused by NSAIDS is actually minimal change disease with nephrotic syndrome. A bunch of other medications have been implicated too, the above is not a comprehensive list.

Treatment

In general there are not many different treatments for glomerular kidney diseases. Most regimens include the following (either alone or in combination).

- Steroids

- Calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine or tacrolimus)

- Mycophenolate Mofetil

- Cyclophosphamide

- Rituximab

How I treat Minimal Change Disease

For most patients:

- Steroids

Initial Dose: Prednisone 1 mg /kg (up to 80 mg) daily. Some people say 2 mg/kg (up to 160 mg) every other day is better tolerated.

As an aside, I am not a fan of using this high dose of steroids for most kidney diseases. I am more prone to go straight to a regimen of lower dose of steroids along with another immunosuppressant. Minimal Change Disease is the one exception for the following reasons:

- The duration of high dose steroids is typically short. They say 50% of adults respond within a month, my experience is most patients respond in this time frame. Once response occurs the steroids can be tapered over 2-3 months.

- The patients are typically younger with less comorbidities.

Although guidelines say you can use the high dose of prednisone for up to 4 months, before calling them steroid resistant I would not do this. I find that using prednisone at a daily dose of 60 mg or higher for more than 2 months will universally cause problems (like Cushingoid). Also there can be a lot of complications especially in older patients (I have seen some severe gastrointestinal bleeding for instance).

Taper: There usually is a quick response to this dose of steroids (50% of adults respond within a month). Remissions are abrupt too. Not a lot of middle ground, you either have the full deal or not.

- Once remission occurs, taper prednisone slowly over 2-3 months.

- For patients with a contraindication to high dose steroids. There are some patients (for example an older patient with severe diabetes) for whom you don’t want to even use a 1-2 month course of high dose prednisone. In this case there are 2 options.

- Calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine or tacrolimus). Cyclosporine was the first of these medications so a lot of regimens were developed with this. Tacrolimus came later and is generally thought of as better for kidney transplant immunosuppression. Newer regimens include this.

- Cyclosporine: 3-5 mg/ kg day (divided in 2 doses, dosed q 12 hrs with target trough 150-200)

- Tacrolimus: 05-0.1 mg/kg day (divided in 2 doses, dosed q 12 hrs with target trough 4-7)

- Use along with low dose prednisone (0.3 mg/kg/day). This dose of prednisone (typically 20-25 mg per day) is better tolerated than 60 mg per day.

The problem with calcineurin inhibitors (in my experience) is the patients are more prone to relapse when they are weaned. Therefore the regimens are longer. The initial dose is used for 12-18 months, then ½ dose for another 18-24 months, then wean over 4-6 months.

- Mycophenolate Mofetil (MMF)

- Initial dose 500 mg twice a day. If tolerated (no GI side effects) then increase to 1000 mg twice a day.

- Use along with steroids (prednisone 0.5 mg/kg day).

In my experience this medication doesn’t work very well for this condition. Like with calcineurin inhibitors, if you use this medication you’re in it for the long hall (12-18 months with a very slow wean over another 18-24 months). I would definitely try a calcineurin inhibitor before MMF.

For patients who don’t respond to steroids within 2 months. In this case I would wean the prednisone and try a steroid sparing regimen.

- Calcineurin inhibitor (regimen as above)

- Mycophenolate Mofetil (regimen as above)

- Cyclophosphamide (see below for regimen)

- Rituximab (see below for regimen)

For patients who relapse. For minimal change disease the problem isn’t a lack of response to steroids (50% of adults respond within a month as noted above), the problem is:

- Relapse after steroids are weaned or

- Steroid dependence with relapse when weaned to a low dose (ie < 20 mg).

Here are your options:

- Repeat course of steroids. If the patient relapses rarely and responds quickly to steroids, another steroid course is not a big deal. However for a patient who relapses frequently the cumulative steroid dose can be problematic.

In these cases there are 2 other options.

- Cyclophosphamide: In my experience this medication is perhaps the most likely to result in a durable remission for glomerular diseases. It’s true there are some important toxicities to be aware of including:

- Infertility: An important consideration in young women

- Leukopenia/Infections. Monitor CBC twice a month. Decrease dose if WBC < 3.5

- Secondary malignancies (bladder, myelodysplastic syndrome). The risk of these is based on the cumulative cyclophosphamide dose. The use in glomerular disease is typically no longer than 6 months. There is a low risk for these conditions with that cumulative dose. I typically monitor for hematuria, however. If new hematuria would refer for cystoscopy.

- Initial dose is 2 mg/kg

- Rituximab: This has been a trendy drug to use in glomerular diseases. Even though minimal change is thought to be mediated by T cells, this B cell drug can be effective.

- Dose 1 gram with a repeat dose after 2 weeks

- Can give a maintenance dose every 6 months

- Can Montor CD19 counts

Summary

Minimal Change disease is a cause of nephrotic syndrome in adults. Most often idiopathic, with abrupt onset of full blow nephrotic syndrome. Often steroid responsive, although frequent relapses may require use of a steroid sparing regimen.