Table of Contents

Dialysis access is the lifeline for patients on dialysis. The goal is to have a durable arteriovenous access (ideally an arteriovenous fistula). However, this is not always possible. The majority of patients initiate dialysis with a catheter and there may be complications that impair the use of the arteriovenous access in prevalent patients.

The goal is to keep the duration of catheter exposure as short as possible.

Types of Dialysis Catheters

-

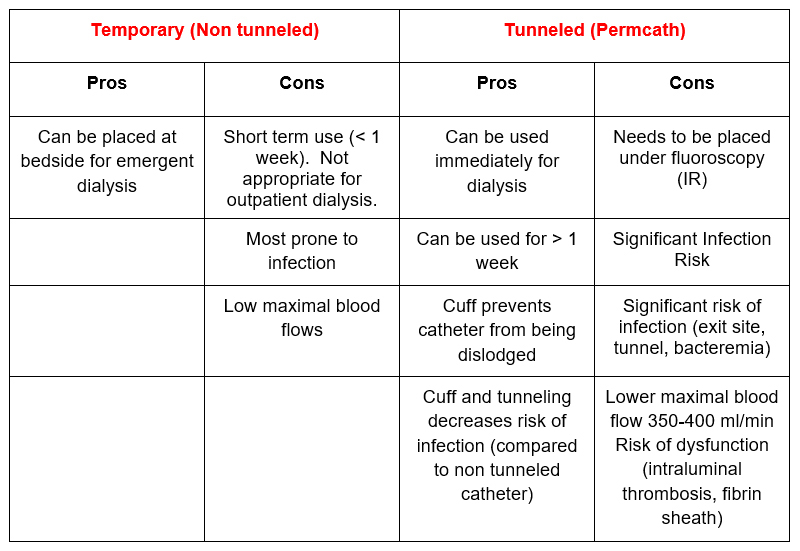

Temporary (Non tunneled)

- Catheter enters directly into vein

-

Tunneled (permcath)

- Catheter is tunneled under the skin (does not enter directly into vein) with a cuff at the exit site

Dialysis Catheters: Things to Know

- Placed in the Internal Jugular or Femoral Vein. Many think that permcaths are in the subclavian because they exit under the clavicle. They are not. They are in the IJ and tunneled under the skin to exit under the clavicle. The subclavian vein should not be used.

Why Not? Because subclavian catheters can be associated with central venous (subclavian vein) stenosis. This narrowing may not be a big deal in general, but it can screw up the possibility for a functional arteriovenous access (fistula or graft) in the future. The higher venous flow with an AV access in the context of a central stenosis may lead to back pressure with resultant significant arm edema and/or access dysfunction.

Common Catheter Complications

-

Infections

- Can be severe and life threatening: Bacteremia with risk for sepsis, endocarditis, epidural abscess

- You get a call from the dialysis nurse that a patient with a catheter has a fever.

-

-

- Order blood cultures and antibiotics. I typically order Vancomycin (as staphylococci are the most common infections) and often add a cephalosporin with pseudomonas coverage (Ceftazidime or Cefepime) until culture data are back.

- If patient is toxic, refer to the ER. For toxic patients the catheter should be promptly removed.

- You get a call from the dialysis nurse that the patient’s blood cultures from the last treatment are positive. The patient is currently asymptomatic.

-

-

-

- Repeat blood cultures and continue antibiotics (narrowed to organism). Continue for 2 weeks after line exchange. Surveillance cultures 1 week post treatment.

- Arrange for catheter exchange. I do not treat catheter infections “through” the line”. Bacteremia (unless deemed to be a contaminant) should be treated with line change or exchange. In most cases the line can be safely exchanged as an outpatient. Times when the catheter should be removed (not exchanged).

- Patient is toxic

- Some recommend removal for S Aureus infection

-

- You get a call from the dialysis nurse that the catheter exit site has drainage.Check to make sure the tunnel does not have signs of infection

-

- Order mupirocin (bactroban) to be given with dressing changes by dialysis nurse

- Consider blood cultures and systemic antibiotics. (I typically order cultures and 1 dose of Vancomycin pending the results).

-

Catheter Dysfunction

- A dialysis catheter needs to be able to maintain a minimal blood flow of 300 ml/minute to be functional. One should expect a blood flow of 350 ml/minute for most tunneled catheters. Some can achieve a blood flow of 400 ml/minute. This is the maximum that can be achieved routinely. Reasons for catheter dysfunction are:

- Poor position

- Mechanical kinking

- Intraluminal thrombosis

- Fibrin sheath (encases outer portion of catheter)

- You get a call from the dialysis nurse that the catheter doesn’t work. It is not possible to achieve blood flow (the venous or arterial pressure alarms. Steps to take.

-

- Review troubleshooting. The nurse may have already flushed the catheter vigorously and/or attempted to “switch the lines”, that is pull from the blue “venous” port and return through the red “arterial” port.

- Administer an intraluminal thrombolytic (tpa).

- Arrange for catheter exchange with disruption of the fibrin sheath. Can be done as outpatient by interventional radiology or nephrology.

An interventionist may tell you that the catheter works because they are able to freely aspirate and flush the catheter. That may be true, but if the dialysis nurse cannot get the catheter to function it doesn’t matter. Being able to aspirate and flush a catheter is one thing, being able to achieve a blood flow rate of > 300 ml/minute is something else.

Summary

Dialysis catheters are a necessary, but not ideal way to provide access for dialysis patients. Keeping the duration of catheter exposure to a minimum is an important way to provide optimal care. Complications such as infections and dysfunction will occur so knowledge of the management of these complications is important.