Table of Contents

I’m going to review 5 sets of equations that I often use in the evaluation of hospitalized patients with acid base and electrolyte disorders. I believe that familiarity with these is not only helpful for board testing, but also in clinical practice.

Although there are apps that make it easy to do these calculations, just enter the numbers and get the results, I’m old school and believe there is value in understanding and knowing them. First, with familiarity it can be easy to eyeball the numbers and get a ballpark estimate. Second, if the calculation on the app doesn’t make sense with the clinical picture you can do the calculation and confirm the results.

Anion Gap

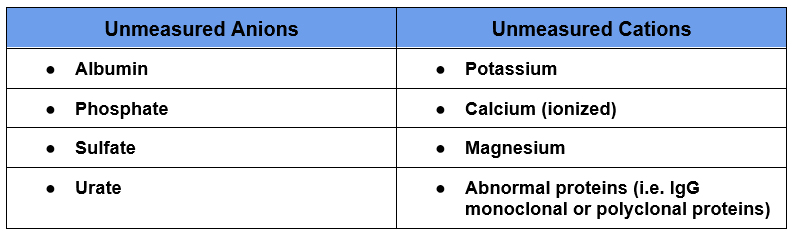

The anion gap is the difference between unmeasured anions (negatively charged ions) and unmeasured cations (positively charged ions).

Unmeasured Anions – Unmeasured Cations

In reality all of the positive and negative charges in the body are equal. However not everything is measured or used in the calculation. There are typically more unmeasured anions than cations. A normal anion gap is between 3-14 depending on the specific lab. It may vary by laboratory as the sensitivity for measuring Cl– differs depending on the assay used.

The formula takes the main cation in the plasma which is sodium (Na+) and subtracts the main anions, which are chloride (Cl–) and bicarbonate (HCO3–).

Na+ – (Cl– + HCO3–)

It will be elevated if there is another anion present such as lactate or beta hydroxybutyrate.

Why it Matters

Not only does calculating the anion gap help formulate the differential diagnosis by distinguishing normal and elevated anion gap metabolic acidosis, it may be the only clue that an acid base disorder is present. In a mixed acid base disorder it is possible for the pH, pCO2 and serum HCO3– to all be in the normal range. This is a classic test question. If the anion gap is > 20 a metabolic acidosis is present.

Metabolic Acidosis – Approach to Diagnosis | BCNephro

Corrected Anion Gap

The main unmeasured anion is albumin. For this reason the anion gap can be corrected for hypoalbuminemia.

Corrected anion gap = Anion Gap + [2.5 x (4.5 – albumin)]

The main unmeasured anion in the body is albumin. If there is hypoalbuminemia the baseline anion gap will be low and the presence of an increased anion gap may be masked, as an increase from the low baseline may still be in the “normal” range.

Compensation in acid base disorders

Why it matters

If the appropriate physiologic compensation doesn’t occur it suggests the presence of a second primary acid base disturbance. These equations are necessary to diagnose mixed acid base disorders on exams and provide a clue of the presence of additional diagnoses in clinical practice.

Metabolic Acidosis

For Metabolic acidosis the Winter’s formula is used:

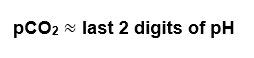

There is also an easy way to estimate this

Example: If the pH is 7.25 the pCO2 should be around 25

Metabolic Alkalosis

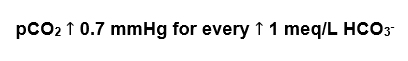

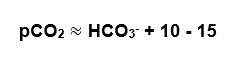

For Metabolic alkalosis:

Example: If the HCO3– is 34, normal being 24, the pCO2 should increase by 10 x 0.7 and be 47

The easy way:

In the above example, the pCO2 is 13 above the HCO3– and is in that 10-15 range.

Primary Respiratory Disorders

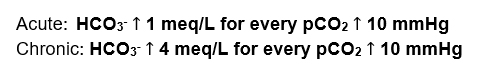

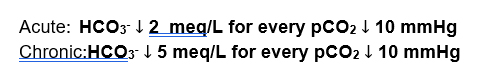

Unlike respiratory compensation for metabolic disturbances which is almost immediate, metabolic compensation for primary respiratory disorders takes time. Therefore, there are different calculations for acute and chronic respiratory acidosis and alkalosis

For Respiratory Acidosis:

For Respiratory Alkalosis:

The way I remember which is which is this. I consider respiratory acidosis to be more severe than respiratory alkalosis so it would make sense that the compensation would be greater for respiratory acidosis. But it’s not, I remember it because I consider it ironic.

Understanding Acid Base Disorders | BCNephro

Osmolar gap

This is the difference in the measured and calculated osmolarity.

Measured osmolarity – Calculate osmolarity

Normal is 6, abnormal considered > 10.

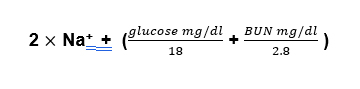

The measured osmolarity is simple enough, just order the test through the lab. The calculated osmolarity takes into account the major osmotically active substances in the blood which are sodium and its associated anions, urea and glucose.

Why do you divide the glucose and BUN? Because we need to convert the units from milligrams/deciliter (mg/dl) to millimoles/liter mMol/L). Sodium is already in mMol/ liter (actually it’s in meq/dl, but it’s a monovalent cation so mMol and meq are the same). The way you convert mg to mMol is to divide by the molecular weight and the way you convert dl to liters is to multiply by 10.

mMol = mg/moles

Liters = dl x 10

The molecular weight of BUN is 28, so dividing by 28 and multiplying by 10 is the same as dividing by 2.8.

The molecular weight of glucose is 180, so dividing by 180 and multiplying by 10 is the same as dividing by 18.

This can be relatively easily eyeballed by dividing by 3 for BUN and 20 for glucose which will give a close estimate in most cases, typically within 2.

For BUN and glucose levels lower than this the difference will be less.

If there’s any uncertainty do the calculation.

Why it Matters

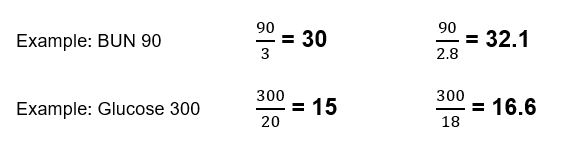

2 reasons. First it is used to screen for the presence of a toxic alcohol ingestion. It should be done in any patient presenting with an increased anion gap metabolic acidosis. Since people who drink methanol or ethylene glycol often also drink regular alcohol, ethanol can be included in the calculated osmolarity. The molecular weight of ethanol is 46, so divide the level by 4.6

If the osmolar gap is > 10 in this context a toxic alcohol ingestion should be suspected.

Toxic Alcohol Ingestions | BCNephro

Second, it can be a clue to pseudohyponatremia. In this situation, the sodium is artifactually low so the calculated osmolarity, which uses the sodium will also be artifactually low.

Hyponatremia: What the labs tell us | BCNephro

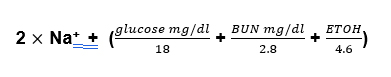

Free water deficit

Why it Matters

It’s used in hypernatremia to give an idea of how much free water needs to be repleted. Doing this calculation will often show that more water than initially is prescribed is necessary.

The total body water varies based on age and gender, because there is more water in muscle than fat.

An estimate used for calculations is:

- Weight x 0.6 for men

- Weight x 0.5 for women or older men

- Weight x 0.45 for older women.

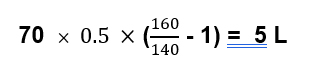

So for an older 70 kg man, with a sodium of 160, the free water deficit would be 5 liters.

Using this equation will typically underestimate the amount of water necessary to correct hypernatremia because it doesn’t take into account ongoing water losses. These can be insensible losses, but a significant amount of free water losses can be in the urine.

This is where the fifth equation is useful

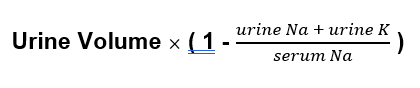

Electrolyte free water clearance

This tells us how much free water is excreted in the urine.

Potassium counts because potassium exchanges for sodium when it goes from the extracellular to intracellular space.

Why it Matters

Understanding this concept is important in both hypernatremia and hyponatremia

Hypernatremia:

In addition to replacing the free water deficit, replacing ongoing free water losses is necessary to correct the serum sodium. Significant urine free water losses occur with an osmotic diuresis and with resolution of prerenal azotemia.

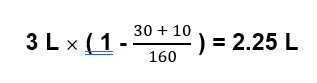

Example: Serum na 160; urine sodium 30; urine potassium 10, urine volume 3 liters

In this case you would need to give 2.25 liters of water just to prevent the sodium from worsening.

Hyponatremia:

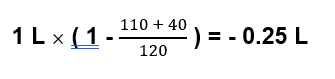

In situations like SIADH it is possible to have a negative free water clearance, that is excrete hypertonic urine.

Example. Serum na 120; urine sodium 110; urine potassium 30

In this case for every liter of urine excreted the body retains 250 ml of free water.

In this situation, giving isotonic intravenous fluids like Normal Saline would make the sodium worse and hypertonic saline would be necessary to correct the hyponatremia.

Sodium What is Normal? 140 vs 154 | BCNephro

Summary

Knowing these equations is necessary for assessing acid base and sodium disorders, both in clinical practice and on exams.